In my home country Germany, freedom of science is guaranteed by the Basic Law, as the constitution is called. When the Academic Freedom Act came into force in 2012, it increased self-governance of non-university research institutes in addition to universities. In contrast, the science sector in Japan has traditionally been strongly controlled by the ministries. Recently however, there is a push for changes and improvements.

Historic developments

In my first column, Japan’s Science and Technology – Rooted in History, I have described the historic development. In Europe, universities were founded already back in the middle ages, long before there was a ministry of education or research ministry.

The word university comes from the Latin universitas magistrorum et scholarium and carries the meaning of a community of scholars and teachers. It implies open exchange rather than purpose driven activity. Universities were founded out of the striving for knowledge and enlightenment, and they were established as independent institutions where independent minds should work and be educated.

Japan was closed until the 1870s. It had a window to the outside world, but the first universities and most research institutes were founded during the Meiji Restoration, when the country finally opened up and modernized. Consequently, it was a plan designed and executed by the Ministry of Education, which was founded in 1871. They had a goal in mind: To catch up with the knowledge of Western countries that was needed to quickly industrialize Japan.

This goal-driven approach to universities and other scientific institutes remained current throughout the 20th century up to today. In my article Japan – The Nation based on Science, I mentioned that in the 1980s, when Japan was under pressure from the outside to do more basic research, the ministries ordered their science organisations to do so.

The goal changed after the bubble economy had burst in the 1990s, when the ministries demanded more innovations – nowadays, even universities are asked to do more projects in collaboration with industry. This change, however, is not always easy to follow for science organizations.

At the same time, Japan has enacted the Science and Technology Basic Law, which states the importance of science for a resource poor country. The government supports this sector and gives it a role of ample importance. If interaction and communication runs well between the science sector and the ministries, the focal points can be adapted mutually.

Free science and the Academic Freedom Act

As for comparison, how is the situation in Germany? There, academic freedom is guaranteed by the constitution under the assumption that freedom is important for scientific discovery. Article 5 of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany states: “Arts and sciences, research and teaching shall be free. The freedom of teaching shall not release any person from allegiance to the constitution.”

This freedom essentially means that no authority should decide what is to be learned. Coming from past experiences, it is thought to empower science. It is also the basis for the practice of academic self-governance, which grants universities full control of their internal affairs.

In 2012, the German government enacted a new law granting more self-governance also to non-university institutions. The Academic Freedom Act allows the autonomous usage of third-party funds acquired, among others, through industrial research projects. Besides for construction or equity, these funds can even be used to pay salaries that are higher than those for public employees and thus make it possible to employ outstanding people.

It is expected that people are free in their minds and use this freedom in a responsible and constructive way. High potentials, which every scientific institution would like to attract, require such freedom. However, the responsible use cannot always be guaranteed and requires a balanced monitoring by public institutions.

In Japan, research institutions are under comparatively more direct governance. Freedom depends on negotiation between actors. What does this mean for freedom of scientists?

Nails that stick out are hammered down? Maybe….

“Hammering down nails that are sticking out” is a popular picture used among foreigners when talking about Japanese culture. It refers to how Japanese society enforces conformity instead of individuality.

Yet even in Japan the common consensus is that education should shift toward more individuality, because it is thought to lead to more creativity in people. As a result, the phrase is less typical nowadays, but continued efforts have to be undertaken to continue changing the framework and peoples’ minds.

Conclusions

Although it is true that in reality science may sometimes not be as free as it supposed to be, in many countries such as Germany, freedom of science is intended to set free creativity and a striving for research. In Japan, freedom of science is not mandated by law, yet the given framework provides at least some degree of freedom.

A very positive factor is that the importance of science is common understanding. The government’s Fifth Science and Technology Basic Plan is in force since April this year and strives to set free more innovation and with it more creativity. Among the main points to achieve are open innovation and internationalisation, which also need an open and international atmosphere.

Japan has created an excellent scientific basis for this, but in my opinion authorities should dare to give more room for self-governance. I am certain that Japanese people will naturally use this freedom in a responsible way.

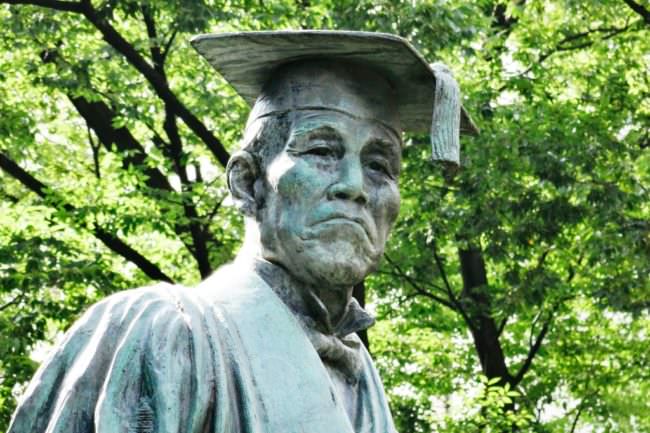

Photo credit: Top visual “Waseda University, Waseda Campus: Statue of Okuma Shigenobu” by Dick Thomas Johnson via Flickr

No comments yet.